October 29:

Ramona is sick, which is bad, as this is the Halls' big day off, or

rather, one of two -- their weekend in Madagascar. Jungle, lemurs,

etc. She'll be home convalescing while we gallivant. Doug says that

she's a tremendous reader, so she'll have plenty to do.

I went to bed last night at 10pm, which is a little late for me these

days. I am in bed by 8:30 some days. I wake up, generally, around

4am, feeling refreshed. I force myself back to sleep for an hour or

so, then putter around until it's time for SALFA's arranged ride or

meet-up or something, which is anywhere between 6am to 8:30. The 9am

pickup for the Rotary celebration should be the only one that late.

So I've been getting between six and eight hours of sleep a night, and

feeling well.

But this morning, I woke up at 8am. 7:50am, actually. And the pickup

time was 8am. Firstly, I had to throw on clothes and run down to

apologize, but secondly, I'm a little shocked: I just got almost ten

hours of sleep. That never happens. This leaves me thinking:

1. Hey, cool.

2. My jet lag is clearing up, and I have to make up some hours.

3. I'm sick.

Well, I know I'm sick. I've had a little diarrhea for days, though

very low level. It started after eating at the only semi-fly-ridden

restaurant where I had rice, pork and casaba leaf mush -- a dish I

recommend. But I haven't got a fever, and I have no other symptoms,

so I don't think of myself as sick, so much as adjusting to some new

friends. I'm hoping that they're bacterial, rather than paramecial or

amoebic.

Well, I feel fine, so off we go, Hasine driving, and we're Eastbound.

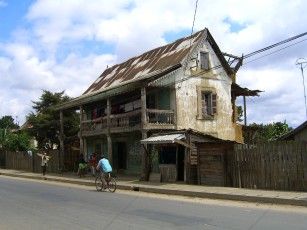

The road East is very different from the West one. First, there's a

lot more city to go through. Second, the city doesn't end at the city

limit, here. We pass a sign which says, in French, "exiting

Antananarivo", but the city keeps on going. In the West road, you hit

markets, then abject poverty. On the East, the people are more

affluent. We pass a compound of seventh day adventists, for example,

it's big and looks nice. There are real architectural objects here,

with brick and some glass. On the West road, things quickly turn into

huts, and while there are plenty of brick buildings going West,

they're the minority.

Soon the road turns rural, and for a short time, we see the rice

paddies and brickworks that the road West led us to expect. But it

all seems nicer, somehow. I attribute this to two things:

1. The road East is mountainous, so the view is just a lot nicer.

It restrains the space, so you can't just take the plain and be done,

you have to terrace, plant different crops, graze animals on the

slopes, etc.

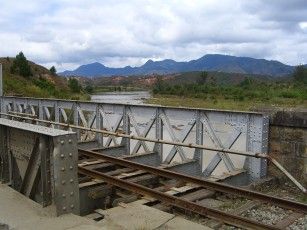

2. The train goes through here, so there's more commerce and

access to markets and goods than there is on the road to the West.

The train is disused, right now, but it used to work, and they're

working on getting it back on-line. Mind you, it hasn't run WELL in

25 years.

We pass a modern brick factory which is a great contrast to the

home-grown brickworks all around Tana. They make blocks, here, with

space inside, like cinderblocks in the US. They're earthware-colored,

and are used to build walls quickly, as they're larger and lighter

than bricks. Today and in the passed day of driving we have seen

perhaps a hundred family brickworks, with their characteristic

house-like kilns for baking the bricks hard. We've seen men hucking

bricks back and forth, stopping the bricks in mid-air as if by magic,

so attuned are they to managing the arch of the toss and the and

weight of the brick -- I'm not kidding: it looks like a magic trick,

but I expect it's just something that comes naturally after about a

hundred thousand brick tosses.

But I wonder what the capacity of all these family brickworks is

compared to this company's? Why make lighter bricks that minimize

labor, if people can buy bricks so cheaply from the poor family

brickworks? Why use larger blocks to minimize labor when labor is so

cheap? The answer has got to be, in part, that with automation

combined with cheap labor, these bricks are priced competitively with

the hand-made ones of the family brickworks. And since there's

capital investment, here, they must be churning out a lot more of them

per laborer/square meter of factory space.

If that's the case, why not build 10 of these, put all the brickworks

out of business and get that land and those people doing something

else? Something which makes the same or more money, and which helps

the community more?

A lot of bricks are made, here, and there's good reason. Madagascar,

and Tana especially, is growing like gang-busters. Population doubles

here every 20 years or so. For the non-binary crazy, allow me to

point out that in 60 years, there will be EIGHT times as many Malagasy

as there are today, and in 80 years, SIXTEEN times. There not hurting

for space, today, but as a westerner, I know that the key to

prosperity is not more kids but more efficiency.

Kids are a pyramid scheme. Have kids, put them to work, and make

enough money to support the family. Without kids, and a lot of them,

you don't bring enough money in. Then they take care of you when you

get old. "Children", Doctor Olivier quoted as a Malagasy proverb to

me a few days ago, "are money."

But if you can't make ends meet without the income of your children,

and the same is true for them, then the cycle has to go forward at

this break-neck pace until all the resources are allocated. Then

comes efficiency or starvation. Anyone can see that with efficiency

comes affluence, and with that, health. Why not work on efficiency

now? First, because there's little money to spend on efficiency, and

second, because you don't fix something until it's utterly broken.

The world bank will be here for efficiency once it's too late, I

promise you.

We drive for an hour or so, then hit the mother of all traffic jams.

Trucks are lined up for at least a kilometer, probably three, and not

going anywhere. As a more agile vehicle, we leapfrog forward, but

wind up stopped for twenty minutes or so, as a line of trucks comes

the other way -- the road is only two lanes after all.

One trucker we pass is not yet eating his lunch, as he squats under

his truck, but is in the process of COOKING IT. With a fire. Under

his truck. He knew he was going nowhere anytime soon.

The log-jam turns out to be a container which fell off a truck at a

particularly sharp switchback and once we're past that, we're all set.

But during that time, we get our first taste of suffocation by

car/truck exhaust. More on that later.

We drive for a total of three hours, until we reach a nature preserve.

After paying for a day pass, we get a guide who Hasine knows. He's

not bad. The park's paths are paved with stone, so it's easy walking,

but a little on the pre-chewed side. We see some good wildlife,

though, including two kinds of lemurs and I got a little movie of 'em.

Read a nature book for more on the lemurs. (Lords and Lemurs by

Alison Jolly is good.) Here's what little I was told about what I

saw. The white/gray (sifaka) ones are monogamous. They live 50

years. The red lemurs are not monogamous and live 30 years. The red

ones are really cute. They make little piggy noises, and are easy to

imitate, so you can get their attention and relax them at the same

time by grunting. I got too close, I know, both for their health and

mine. I am a BAD eco-tourist. Bad Paul!

We have some lunch afterward, at a tourist-aimed hotel with an

expensive restaurant. I lay down eighteen dollars or so for lunch for

the three of us. That's not so bad.

But after getting a move-on back, I start to feel ill. By the time

we're half-way home, I need to ask Hasine to pull over. While Doug

and Hasine wait, I scurry up a hill and behind some bushes to do some

dirty-work. It solves my immediate problem, but I'm still queasy and

feel that that urgency will recur.

Hasine is a great driver because he's a professional. Before he got

the job with MELCAM, he was a taxi driver. He owns one of the bizarre

looking little Citruens we see working as cabs. (There's some

disagreement between people I've asked as to whether these Citruens

are 30 or 50 years old. I know I saw ones just like them in old black

and white films set in Paris.) Cab-driving is the family business --

his father still drives a cab. When I asked whether it pays well,

Hasine laughs and shakes his head. No, he answers emphatically.

Hasine sees that both Doug and I are interested in the railroad, so at

the end, he takes a detour and drives us out onto the great plain part

of Tana. Up to now, we've only be up in the hills. It comes as a

great surprise to me how much commerce is down here. The hill is like

the Italy of James Bond movies, with it's twisting roads and little

stairways between streets. The plain is like LA -- flat, fairly

regular and, since we're arriving at 6pm, inundated with smog.

At the compound, we're significantly above that smog. It doesn't take

much elevation. The plain down below is an asthmatic's nightmare --

it would kill my brother or father dead in a few minutes. All these

cars with no catalytic converters. We're in a Toyota Land Cruiser,

but most people drive the ancient Citruens, somewhat more modern

Renaults, or Peugot cars. There are also the bizillion trucks. The

most common manufacturer's logo I've seen on these trucks is Mercedes,

but fine German engineering or not, they all run horribly dirty. The

upshot is a nightmarish gray soup that is very difficult to breath.

But the reason he's brought us here is to see the main railroad

station. It's worth the trip. Big ornate, and very French.

It's always a conundrum for us as to how much to tip. Hasine was a

great driver for the trip. He makes, probably, about $1200 a year.

Should we tip $20? That's a week's pay, almost. Will we economically

destabilize anything by doing so? Certainly we can afford it, and

it's what we'd tip a driver for a day's work in Chicago.

Thanks to my constant diarrhea, I'm in such a hurry for a toilet that

we put off tipping, much less paying for the car in the first place --

the price is on the bill, anyhow, and we won't feel the pain until the

end. I feel bad about it, but I know that when I leave, I'll be

handing out tips like water.